For a first-time list MP who made it into Parliament by the skin of her teeth, and is in a minor party that maybe is or isn’t in government (depending on what day it is and who you ask), Golriz Ghahraman sure gets a lot of attention. I’m loathe to add to it, but her self-appointed role as chief champion of hate speech law reform demands it.

Now, to pre-empt those who apparently consider skin pigmentation determines credentials to comment on this subject, I confess that my skin is some shade of white, though Hitler and his henchmen considered my people most definitely not white, as did the white supremacist gunman who massacred 11 of my people in a Pittsburgh synagogue last year. For those who can see past skin pigmentation, it’s worth remembering Jews (my family included) have a history of persecution and discrimination and that they are still vulnerable; in every Western country where hate crime statistics are maintained, Jews are increasingly disproportionately represented, more so than any other group. I’ve had quite a bit of hate mail (both snail mail and social media) and for those who think lived experience matters when discussing this issue, I believe I have enough of it.

But enough about me. Let’s talk about Ghahraman. There is no doubt she is the target of bigotry. As a country we should all be proud that we have our first refugee MP. The idea that a person who came to the country as a refugee decades ago should be beholden to its beneficence and not participate in democracy in a way other citizens can is repugnant. New Zealand is her home, not her host. It’s abhorrent to suggest she’s a “plant” for Iran, or should return there. It is her democratic right to criticise this country, including its foundational values, if she so chooses, and to argue for a dilution of democratic rights, as she does in championing new hate speech laws.

It is possible, and important, to challenge her ideas on this subject without attacking her because of her identity. If we are to have a mature, nuanced debate about this, a touchstone for the health and robustness of our democratic society, it is incumbent upon those on both sides of the debate to distinguish between attacks on people because of their race or gender and a critique of ideas and actions.

We should have this debate with the presumption that its participants all want the same outcome – for New Zealand to be a safe and inclusive place for all people, and to minimise the chances of such a heinous attack occurring again. But there is a legitimate debate to be had about how to achieve that outcome. It should not just be readily accepted that the best way to protect vulnerable groups is through new restrictions on speech. Questioning that proposition does not mean you worry about or are affected by racism any less than Ghahraman, or are complicit in it, or are a less worthy person than her. Unfortunately, however, those who disagree with and challenge Ghahraman are often attributed with the worst motives, demeaned and smeared.

If Ghahraman wants to engender the public’s trust that this isn’t a censorship exercise, she will need to avoid accusing her critics of white supremacy or privilege, and refrain from threatening defamation with the elitist reminder that she has “a LOT of free legal resource to draw on”. Rather than shutting down debate, she will need to show that she can engage in good faith with the arguments as to the philosophical underpinnings of freedom of speech and the practical problems with further restricting it.

Thus far, Ghahraman’s articulation of her ideas do not withstand scrutiny on even the most superficial level. Perhaps this is why she decided that the best medium to communicate them is in an infantile comic strip. Her statements are not considered, consistent or credible and she provides scant evidence or robust reasoning.

For a start, her conclusion that our liberal laws on hate speech were at least in part to blame for the mosque attacks seems somewhat premature, given that she announced this before the investigation is completed as to how, when and where the gunman was radicalised, let alone before the victims had even been laid to rest.

Also, if you are hoping to persuade people that hate speech should be criminalised, you might first want to offer a definition of hate speech. When Ghahraman was interviewed on Newshub Nation, she was asked upfront how to define hate speech. She waffled around for some time but did not offer a concise definition. She seemed to equate hate speech with group defamation, omitting the crucial point that hate speech laws criminalise speech, while defamation is a civil action with defences of truth and honest opinion.

Personally, I have some sympathy with the view that there is a lacuna in the Human Rights Act (which essentially prohibits incitement to violence against racial groups), and I agree with undertaking a review to see whether it should be extended to protect faith-based and gender-based groups, for example. But if she is thinking that the prohibition should be expanded beyond that, she needs to make the case. Is there any evidence that restricting hate speech works and reduces racism?

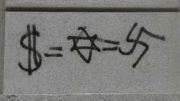

I feel sickened when I see comments that Hitler should have finished the job or “jokes” about ovens and lampshades, but there is a legitimate argument that racism and bigotry can only be combatted if it is in the open, where it can be seen, challenged, and monitored. Banning the expression of hateful ideas does not make them go away. It just means they’re festering in a dark fetid basement. And attempting to suppress them provides fertile ground for the conspiracy theories, resentment and victim mentality that they seem to thrive in.

Historically, freedom of speech applied to enable the oppressed and the disenfranchised to achieve emancipation and equality. It gave those in the civil rights, gay rights and feminism movements a chance to speak truth to power. Any time we are told by those in power that we must cede individual rights for the greater good we should be very suspicious. And we should tread very carefully before we allow those who have the privilege of being in power – like Ghahraman – to determine what identity groups require protection (do Christians, white men and gender critical lesbians?), and to erode the rights of those who are not considered worthy of such protection to say what they want.

Last year, Ghahraman accused Israel of genocide at an anti-Israel rally following a particularly violent day on the Gaza border. Now, plenty of people have accused Israel of a disproportionate response, and had she done so, it wouldn’t rate anything more than a passing mention. In fact, given her self-proclaimed role as the first woman in New Zealand to hold the defence portfolio, I would have been keenly interested in hearing her proffer her expertise on how the IDF should respond proportionately to armed Hamas and Islamic Jihad members hiding behind smokescreens and human shields, attacking a border with the stated aim of breaking through and murdering Jewish communities living close by.

But accusations of genocide are quite another matter. Of course, Ghahraman has no evidence that Israel is committing genocide against Gazans. It would be the first genocide in history in which the target population is increasing rapidly, child mortality has fallen, and life expectancy has increased. She also overlooks that Israel is fighting a war against a terrorist regime that oppresses Gazans and whose stated mission is Jewish genocide. She sees genocidal intent where it isn’t, and ignores it where it is.

While it wasn’t direct incitement to violence, it potentially endangers the Jewish community, who would likely be associated with complicity in genocide. So from what I can decipher about Ghahraman’s views on what constitutes hate speech, based on examples she’s cited and accusations she’s made, she would seem to have fallen foul of her own definition.

The New Zealand Jewish Council, the representative body of the Jewish community, wrote to her about this, and got no reply. Two months later it wrote again, copying in her co-leaders, and still got no reply. This is a deliberate marginalisation of the Jewish community. According to Phil Quin, she also ignored the entreaties of a young Rwandan survivors group, except for one dismissive tweet. It’s hard to imagine a more persecuted people than survivors of genocide. This pattern would seem to suggest her concern for vulnerable communities is rather more selective and politically expedient than she might like people to believe.

It’s hard to take someone seriously who wants to criminalise people for their harmful words, but is not prepared to be held to account for her own harmful words. Such is the far left’s belief in their own moral superiority that, while they point the finger of blame at others with alacrity, they appear to lack the self-awareness and self-reflection that would lead them to at least wonder whether they themselves are complicit in contributing to a divisive and hateful society.

The renowned Jewish American constitutional lawyer and civil libertarian, Professor Alan Dershowitz, who defended the right of neo-Nazis to march in Skokie where many Holocaust survivors lived, posits the “shoe on the other foot” test. It’s much easier to be nonchalant about the importance of freedom of speech when you’re smug in the belief that it’s only speech you disapprove of, and not your own, that will be censored.

NZ has a proud history of stable and long-standing democracy and robust rule of law, but are we prepared to trust that we will always have a benign, moderate government, authorities that do not overreach, or courts that apply a high threshold before they rule that speech should be censored? We now know for sure that our little islands are not immune to the ugly and violent forces sweeping the world, and we take our democracy, the rights that go with it and the institutions that uphold it, for granted at our peril.

– This article was written by Juliet Moses, an Auckland-based lawyer